Thoughts about an incomplete RPG framework

Over the Month of December, I sat down to both conceptualize as well as actually build the beginnings of what I hope is going to be a larger framework that I intend to use to tell stories about people and their communities.

It combines my interest in Tabletop Roleplaying, JRPG battle systems and dungeon crawlers, as well interactive fiction and though I’ve been thinking about these things a lot over the last four years, what currently exists has been the work of the past four weeks and thus is still not fully formed.

However, I still wanted to put some of these ideas out into the world, because I personally found them very exciting, and also because I want to use this as a statement of intent. Both in terms of what games I want to make in the future and in terms of how I think and approach game design as a practice.

This post is going to be broken up into several sections:

First I want to describe the overall purpose of the system, mention some of its main inspirations and lay down some foundational principles that I use to guide myself along as I built out the actual structure.

Then I’m going into detail about the system’s approach to encounter and battle design and after that I talk a bit about the purpose of its “Downtime” segment. As I said, this is not complete. There are a lot of elements that I still need to figure out, or have to change, but again this is as much about stating my intentions as it is about explaining the actual structure of it all.

The Main purpose of this system is to create and tell stories about a group of main characters and how their actions shaped a specific community or region over a pre-determined amount of time. Never are these stories meant to be about special heroes who go out and prevent some ancient evil from destroying the world. This ancient evil might exist and it might destroy the world, but that will always be outside of the players control. The only thing they can affect is the world around them and its shape after the story has reached its conclusion.

My main inspirations so far are:

Videogames: Live a Live, Undertale, Wildermyth, Mystic Quest Legend/Final Fantasy Mystic Quest, Final Fantasy 5, Saga, The Yawhg, Citizen Sleeper, Dragen Age 2, Blue Reflection: Second Light, Dragon’s Dogma (all of them).

Tabletop Rpgs (or their overall systems): Blades in the Dark/Forged in the Dark, Apocalypse World/Powered by the Apocalypse, Belonging outside Belonging, Mobile Frame Zero Firebrands, Heart, The City Beneath.

(Some) of my main principles are:

- The Story always moves forward

- There is no direct failure, but there are consequences.

- Play with scale

- Anything can be a battle

- The Verbs of a character define how they act upon the world

- Actions carry meaning

- Moves exist to break the rules

The overall structure of the game will involve a “Exploration Phase” as well as a “Downtime Phase”. In the exploration phase, the characters will travel their home’s surrounding areas and deal with potential problems and challenges there. During Downtime, the characters will work on personal projects, spend time to recover from any injuries they may have sustained and contribute towards the town’s overall development.

Exploration Phase

The Purpose of a Battle, rethinking failure states

In videogame RPGs, failing in a battle usually means character death, a potential loss of resources, and very often a loss of overall story progress as well.

In a Tabletop RPG, failure can mean many things. It could mean character death, or them sustaining a long-term injury, but at least I’m not aware of any system that requires players to re-do a previous battle, because their characters died. The story takes the failure of the characters and moves forward.

Now the improvisational nature of TTRPGs makes this much easier than the very rigid structure of a videogame, however it is not required for a videogame’s story to grind to a halt, just because the player’s party was unable to defeat a band of Goblins.

However for this to work, you need to apply the consequences for failure elsewhere and have to consider the purpose of the battle itself. When your story is about a group of heroes saving the world, them being unable to carry on, means that the world cannot be saved. If you decouple the outcome of the story from the player’s actions however, you can enact long-term consequences on them, while still moving the overall story forward.

At that point the story itself has to become much less about “Can they deal with a situation”, and much more about “How are they dealing with it?”, “How does it change them?” and “What consequences follow as the result of their actions.”

To go back to the Goblin example. The party losing against the Goblins, could mean the establishment of a local Goblin stronghold and subsequent Goblin related issues. The characters could carry wounds with them that require additional resources to clear, limiting the amount of time they can spend on other things, which in turn will cause more consequences.

There is still a cost associated with losing a battle (as is to winning it, but in a different way potentially), but it doesn’t stop and rewind the story, it just changes it.

The power of Abstraction

The degree of abstraction that the classic JRPG battle interface offers, allows for a very fluid application to both scale of the battle, its narrative framing, as well giving you very potent tools to make general statements about the structure of the world itself. There’s nothing that says a JRPG battle has to be against a threat to one’s physical wellbeing. It can be as much about fighting a Dragon, as it can be about breaking down a door, or fighting the concept of anxiety.

What it does is show you which things are important and can be acted upon, but its framing also says something about the metaphysical nature of the world it inhabits.

Example: Final Fantasy 5 features a range of abilities that are affected by its target’s level. That means that the RPG stat “Level” is an intrinsic quality of every entity in the world that the game inhabits. If it wasn't, the abilities would be framed differently and would not work in the way they do.

Because of this abstract nature, and the connection they create between the game’s narrative framing and its underlying systems, at their most basic level Battles are moments of dramatic significance. It’s where characters and their obstacles act upon each other using their own descriptive qualities and powers.

At the same time, this abstraction can be broken very easily. Changing a handful of words can turn a hero into a coward, a Dragon into a Mouse, or a Mouse into a world devouring monstrosity. This means that the rules of the world can and should be broken. Suddenly the words of an intellectual can inflict physical harm, and the Hero can win at a debate using their Sword.

However, these changes still carry meaning. Bending the fabric of reality should be significant and costly.

There are no useless characters

Playing with scale and abstraction can lead to situations where a character’s main way to act upon the world is ineffective. A Bear will never be interested in a rational argument and you cannot stab the concept of anxiety with a blade.

As stated above, moves and items can bend the rules of the game so that these tools might work, but we can also use the power of abstraction so that instead of doing nothing, the intellectual can “help” the Hero’s attempt to fight the Bear.

In TTRPGs, “helping” is a nice tool to involve characters in situations where they otherwise might be less effective than others. They open the door for more characterization, and inter-character relationship building.

Why have an isolated “defend” command that a player can use to have a less effective character waste their turn, when instead they can provide support to their friends?

Again, actions carry meaning. There’s a difference between, fighting a battle as a series of isolated individual actions, or having characters fight against a threat as a group.

Two characters helping each other says something about their relationship, as does it when they don’t.

Considering that the main purpose of this system is to tell a story about Characters over a specific amount of time and in a very specific place, having means to develop a party’s inter-character relationship within the battle system itself is incredibly important.

Downtime

If the goal of this system is to tell a story about people, their community and their change over time, this means that there has to be a space to move time, and examine how the game’s characters act as members of a community and not just as an isolated group out in the wilds.

There has to be a space for them to recover, to define and work on personal goals and for them to explore their place in their larger community.

This requires a different scale and framing than the exploration part. It shares the same underlying stats and systems, but where these are applied and acted upon has to be different, because everyday life is different from a moment of high dramatic tension.

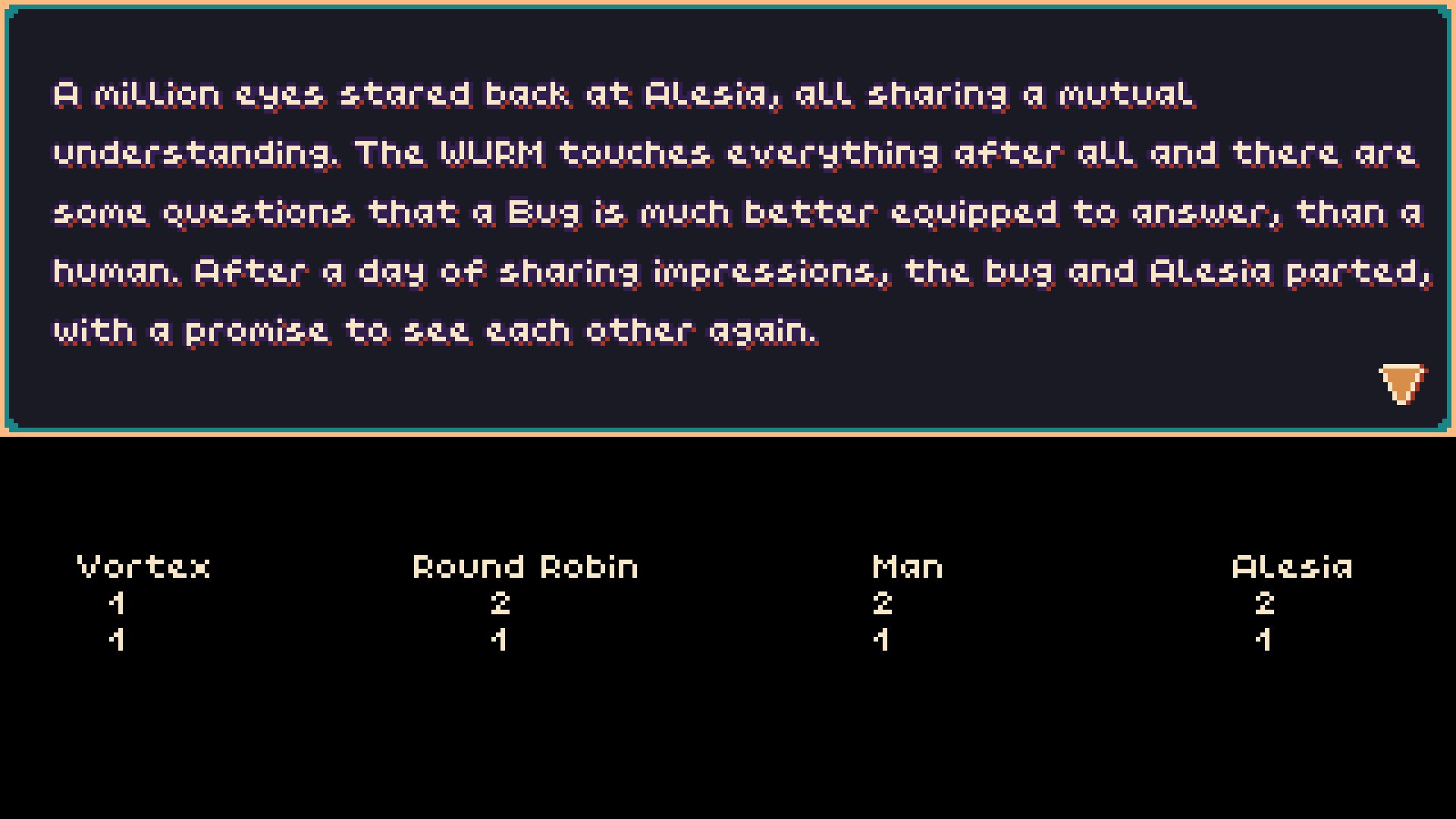

This system working on a different scale and in a different context, doesn’t mean that it’s less important, or detached from the exploratory parts. It is during Downtime where characters have the time and space to recover from their injuries, develop new skills, improve what they already know, and open up potential opportunities for the next exploration phase. It’s a space where the characters get to interact with those around them that are not in the business of adventuring. It’s where they can talk to their neighbours, be roped into sketchy business schemes, commune with the weird metaphysical entity that touches them, or talk about politics in the public forum.

As much as battles are moments of dramatic tension, downtime serves as a way to release that tension, but also to set the stakes for the battles that have yet to come.

(To be continued…)